This is the first in a series of posts exploring the relationship between major monastic houses and their communities. The posts will explore monastic life, the impact of the Abbey as manorial Lord on trade and daily life, the riots of 1327 and the accounts of the obedientaries.

I would like to thank David Gladwin for his assistance in researching and developing these posts, which form part of a larger project looking at the various monastic orders in England.

Monastic communities originated in the Christian Church in response to the need for some men and women to seek God through a life of self-discipline and prayer. The earliest monks were solitary, desert-dwelling hermits, in fourth century Egypt. Their followers became numerous and formed communities around them for worship, protection, and mutual support. St Benedict (c.480-c.550) drew on his experience of leadership of these communities to develop his Rule. This became and remains the most influential guide to the religious life in Western Christianity.

Benedict understood the monastery to be ‘a school of the Lord’s service’. His Rule was written for ordinary people of varied abilities, who wished to serve God in a monastic community. He counselled moderation, aiming to build up the weak and spur on the strong. Allowing all to climb the ladder of perfection, according to their abilities. The purpose was to create a community with the following objectives:

- Stability – all members were committed to the community.

- Conversion of manners – spiritual transformation according to the pattern of Jesus Christ.

- Obedient – freedom from self-will being a pathway to God.

- Free from worldy goods – no personal possessions; all property is given to the community.

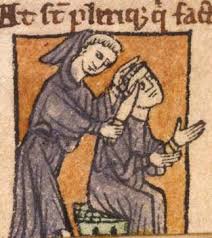

The Rule also provides a structure for the practical life of the community. It provides a framework for the management of the community, how to elect the abbot, appoint the obedientaries (1) and manage conflict. It also proscribes the order of daily living, the times of prayer, work and rest. The houses were expected to be hospitable, welcoming all guests as they would Christ. Benedict describes the chief task of the community as the “opus Dei,” or Work of God. Seven ‘hours’ of communal prayer at set times through the day and night. Benedict envisaged an average of four hours liturgical prayer, four hours of private prayer and spiritual reading, and six hours manual labour per day. Originally the communities were self sufficient, the monks working to provide for the material needs of the community. However as time passed they began to utilise lay brothers (2) and paid servants to do manual work.

In the medieval period, monasteries had crucial social functions, spiritually and charitably. Monks were “spiritual soldiers”, of greater importance than lay armies. Their battles were spiritual, fighting supernatural enemies, such as demons. The monastery symbolised a spiritual castle, with gatehouses and walls to keep people out. And the community in. It was expected that the nobility would found or support monastic houses. Their gifts of land and money given in return for prayer for their temporal and eternal welfare. And the souls of their dead, reducing the time spent in Purgatory. The vocation was as honourable as any secular calling, younger sons and daughters of major families were often encouraged to take holy orders. Many Abbesses were highborn women, who had been trained in estate management from childhood. For the men, their monastic education opened up opportunities to exercise the highest offices in church and state.

Charity was of great importance. Abbeys were provided a range of social services – distributing alms, food and clothing to the poor, providing medical care(3), and education (4). Monastic schools were one of the few means of social mobility. Poor boys of ability had a conduit to the highest offices in the land. Monastic libraries preserved the knowledge of classical antiquity and the Islamic world, for succeeding generations. Corrodories allowed people to either buy themselves, or their servants a place in a monastery for their old age. This would provide them with a small room to live in, basic furnishing and access to food. This accommodation could either be within or without the monastery wall. It was a system that at times was open to abuse, with the pensioner bringing a large family along, or allowing “questionable women” to stay.

Monasteries were hubs of daily life, their spiritual and charitable aims drawing people in. Pilgrims sought out their miracle-working relics, a mainstay of popular religion. Abingdon had a large collection of relics, including those of St Vincent of Saragossa (5). The ‘Black Cross’ of Abingdon, was believed to have been fashioned from a nail of the True Cross. Their lands and property, gave them power over the wider community. This, along with tithes and offerings gave the monastery a healthy “spiritual income”. Its “lay income” came from its function as the manorial lord for much of the town and its environs. The Abbey controlled the trade that took place, running the market and holding it at its gates. It also ensured it was the only church in the town permitted to bury the dead. Local resentment was often aroused by the high handed actions of some of the Abbots.

Monasteries were hubs of daily life, their spiritual and charitable aims drawing people in. Pilgrims sought out their miracle-working relics, a mainstay of popular religion. Abingdon had a large collection of relics, including those of St Vincent of Saragossa (5). The ‘Black Cross’ of Abingdon, was believed to have been fashioned from a nail of the True Cross. Their lands and property, gave them power over the wider community. This, along with tithes and offerings gave the monastery a healthy “spiritual income”. Its “lay income” came from its function as the manorial lord for much of the town and its environs. The Abbey controlled the trade that took place, running the market and holding it at its gates. It also ensured it was the only church in the town permitted to bury the dead. Local resentment was often aroused by the high handed actions of some of the Abbots.

Farming was an important aspect of monastic life. Granges, or monastic farms were run largely by lay brothers who tilled the land and tended the crops. They also raised their own sheep and participated actively in the wool trade. Abingdon was no exception and as the chief landowner and controller of the market, would buy up wool from smaller landowners and tenants. This wool would then be graded and stored, ready for the fleece fair, where it would be sold at a profit. Food was also obtained from the tenants as tithes. All major monasteries had a tithe barn, where a tenth or fifteenth of all crops were collected and stored, for the use of the monastery.

Abingdon, like other monasteries employed lay workers. Through its multiple functions it inspired craftsmanship, artistic, musical and technical innovation and excellence. This was most notable during the abbacy of St Æthelwold (953-963). Joining with St Dunstan of Canterbury and St Oswald of Worcester, he led the revival and reform of English Benedictine monasticism. A great innovator, the chroniclers credit him for introducing the exemplary chant technique from the Abbey of Fleury in France. He installed an organ and founded the bells. He built a monastic church furnished with stone sculpture and gold and silver metalwork, which reflected dignity and splendour. He was responsible for civil engineering, digging a leat from the Thames to power the monastic watermill. He was also a leading statesman, scholar, and teacher.

Revival and reform were important as monastic communities sometimes lost sight of their founding principles. New stricter orders such as the Cluniacs and Cistercians developed as a result, later experiencing similar problems. Despite the accusations of endemic corruption, at the Reformation, there is little historical evidence to support this claim. There were scandals, but they were very rare. A few religious houses could live in opulent idleness, but most were workaday communities. Period visitations from the Bishop or Archdeacon rooted out financial irregularities and inappropriate behaviour, and in extreme cases the Pope could remove an incompetent Abbot or Prior.

Revival and reform were important as monastic communities sometimes lost sight of their founding principles. New stricter orders such as the Cluniacs and Cistercians developed as a result, later experiencing similar problems. Despite the accusations of endemic corruption, at the Reformation, there is little historical evidence to support this claim. There were scandals, but they were very rare. A few religious houses could live in opulent idleness, but most were workaday communities. Period visitations from the Bishop or Archdeacon rooted out financial irregularities and inappropriate behaviour, and in extreme cases the Pope could remove an incompetent Abbot or Prior.

The monasteries were also a source of revenue for the Crown, contributing significant sums via taxes. A “Taxiato” was also levied, when the King and / or Pope needed additional monies to fight wars or fund crusades. The monasteries also paid taxes to Rome, with significant sums leaving the country. The appointment of non-resident Abbots, often family members, by the Papacy was problematic by the early 16th century. These men had no interest in running the monastery, instead remaining in Europe and creaming off the profits. Monasteries were land rich, and litigious, often fighting law suits to keep control of properties. Not all their charters were legal, and some fell foul of the law, when this was exposed, paying heavy fines. Ecclesiastical laws gave them protection from the Common Law, but they were subject to Forest Law. There are many record of monastic officials being imprisoned or fined in the Forest Eyre.

Henry VIII’s decision to suppress the monasteries, was in part financial. It allowed him to sell off their lands to raise revenue. The Abbot of Abingdon surrendered to the Crown without protest in 1538, when there were 25 monks left in the community. Little of the Abbey remains today, the gate house, a few walls in the Abbey Park and the market house are the final traces of a medieval powerhouse.

Footnotes

- Obedientaries are senior monks given important roles such as sacrist, cellarer, kitchener.

- Lay brothers were members of the monastic community whose principle function was to work. Often low born, they were excluded from becoming full brothers.

- In Abingdon Abbey ran St John’s Hospital

- The abbey’s school later developed into today’s Abingdon School

- The first Spanish martyr

References and Bibliography

The Benedictines in Britain. (London: The British Library) 1980

Cox, Mieneke. The Story of Abingdon, Part I. (Abingdon, 1986)

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars. Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580. (New Haven: Yale University Press) 1992.

Haigh, Christopher, ed. The English Reformation Revised (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 1987

Hudson, John, ed. Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis. The History of the Church of Abingdon vol. I. (Oxford: Clarendon Press) 2007

Knowles, David. The Monastic Order in England (Cambridge: University Press) 1950

Southern, R. W. Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (Penguin, 1970)

Yorke, Barbara, ed. Bishop Æthelwold: His Career and Influence (Woodbridge: Boydell Press) 1988.

A beautiful article! The Benedictine Rule itself makes for fascinating reading as well, although by the year 1000, many Benedictine monasteries were reformed, Cluniac institutions. SC

LikeLike

Thank you 😊

LikeLike

Excellent work Bev.,are the various parts available together in a different format for longer-term reading and referencing?

LikeLike

Thank you David. I’m planning to put them together into a PDF document that can be downloaded , which I’ll make available with the final post.

LikeLike